How to Read Radial Probability Distribution Graph

The Probability Distributions for the Hydrogen Atom

To what extent will quantum mechanics permit u.s. to pinpoint the position of an electron when information technology is bound to an cantlet? We tin can obtain an order of magnitude answer to this question by applying the doubt principle

| |

to estimate D x. The value of D x will stand for the minimum uncertainty in our knowledge of the position of the electron. The momentum of an electron in an cantlet is of the order of magnitude of 9 ´ 10 -19 one thousand cm/sec. The doubtfulness in the momentum D p must necessarily be of the same gild of magnitude. Thus

|

The dubiety in the position of the electron is of the aforementioned gild of magnitude as the bore of the cantlet itself. As long as the electron is bound to the atom, we will not be able to say much more than well-nigh its position than that it is in the atom. Certainly all models of the atom which draw the electron every bit a particle following a definite trajectory or orbit must exist discarded.

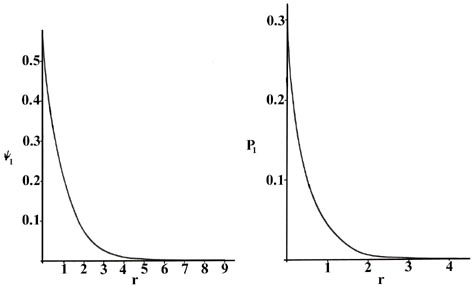

Nosotros can obtain an energy and one or more wave functions for every value of n, the principal quantum number, past solving Schrödinger's equation for the hydrogen cantlet. A noesis of the wave functions, or probability amplitudes y n , allows us to summate the probability distributions for the electron in any given quantum level. When n = 1, the wave part and the derived probability function are independent of direction and depend only on the distance r between the electron and the nucleus. In Fig. 3-4, we plot both y 1 and P 1 versus r, showing the variation in these functions as the electron is moved further and farther from the nucleus in whatever i direction. (These and all succeeding graphs are plotted in terms of the atomic unit of measurement of length, a 0 = 0.529 ´ 10 -eight cm.)

Fig. iii-4. The wave function and probability distribution as functions of r for the north = ane level of the H cantlet. The functions and the radius r are in diminutive units in this and succeeding figures.

Two interpretations can again exist given to the P 1 curve. An experiment designed to find the position of the electron with an uncertainty much less than the diameter of the cantlet itself (using lite of curt wavelength) will, if repeated a large number of times, result in Fig. 3-four for P 1 . That is, the electron volition exist detected close to the nucleus most often and the probability of observing it at some altitude from the nucleus will decrease speedily with increasing r. The atom will exist ionized in making each of these observations because the free energy of the photons with a wavelength much less than 10 -8 cm will be greater than One thousand, the corporeality of energy required to ionize the hydrogen atom. If calorie-free with a wavelength comparable to the bore of the atom is employed in the experiment, then the electron volition not exist excited but our cognition of its position volition exist correspondingly less precise. In these experiments, in which the electron'due south energy is not inverse, the electron volition appear to be "smeared out" and we may interpret P 1 as giving the fraction of the total electronic charge to exist found in every pocket-sized volume chemical element of space. (Recall that the addition of the value of P northward for every small volume element over all space adds up to unity, i.e., one electron and 1 electronic charge.)

When the electron is in a definite energy level we shall refer to the P northward distributions equally electron density distributions , since they describe the manner in which the total electronic charge is distributed in space. The electron density is expressed in terms of the number of electronic charges per unit volume of space, due east -/V. The book V is usually expressed in atomic units of length cubed, and one atomic unit of electron density is then e -/a 0 three . To requite an idea of the order of magnitude of an atomic density unit, one au of charge density e -/a 0 3 = 6.7 electronic charges per cubic Ångstrom. That is, a cube with a length of 0.52917 ´ 10 -8 cm, if uniformly filled with an electronic charge density of one au, would comprise 6.7 electronic charges.

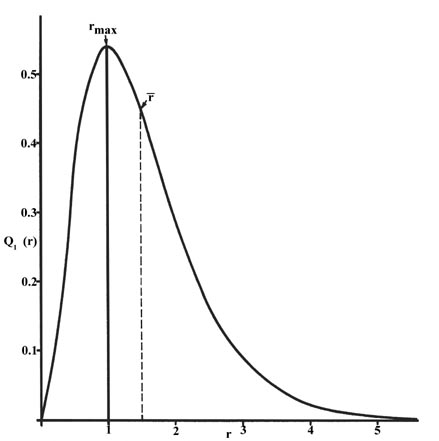

P 1 may exist represented in another manner. Rather than because the amount of electronic charge in i particular small-scale element of space, we may determine the full amount of charge lying inside a thin spherical shell of space. Since the distribution is contained of direction, consider adding upwards all the charge density which lies within a volume of space divisional by an inner sphere of radius r and an outer concentric sphere with a radius only infinitesimally greater, say r + D r. The area of the inner sphere is 4p r 2 and the thickness of the vanquish is D r. Thus the volume of the shell is 4p r 2 D r (Click hither for annotation.) and the product of this volume and the accuse density P 1 (r), which is the accuse or number of electrons per unit of measurement book, is therefore the total amount of electronic accuse lying betwixt the spheres of radius r and r + D r. The product fourp r two P n is given a special proper name, the radial distribution office, which nosotros shall characterization Qnorth (r).

The radial distribution function is plotted in Fig. three-v for the ground land of the hydrogen atom.

| Fig. 3-v. The radial distribution function Qane (r) for an H atom. The value of this office at some value of r when multiplied by D r gives the number of electronic charges inside the thin trounce of space lying between spheres of radius r and r + D r. |

The curve passes through zero at r = 0 since the surface area of a sphere of zero radius is zero. As the radius of the sphere is increased, the volume of space divers by 4p r ii D r increases. However, as shown in Fig 3-4, the absolute value of the electron density at a given indicate decreases with r and the resulting curve must pass through a maximum. This maximum occurs at r max = a 0 . Thus more than of the electronic charge is present at a distance a 0 , out from the nucleus than at any other value of r. Since the curve is unsymmetrical, the boilerplate value of r, denoted past![]() , is non equal to r max . The average value of r is indicated on the figure by a dashed line. A "picture" of the electron density distribution for the electron in the n = 1 level of the hydrogen atom would be a spherical ball of accuse, dumbo effectually the nucleus and becoming increasingly diffuse every bit the value of r is increased.

, is non equal to r max . The average value of r is indicated on the figure by a dashed line. A "picture" of the electron density distribution for the electron in the n = 1 level of the hydrogen atom would be a spherical ball of accuse, dumbo effectually the nucleus and becoming increasingly diffuse every bit the value of r is increased.

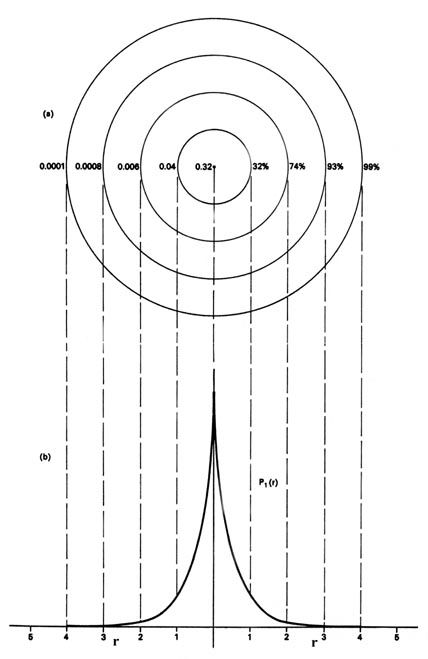

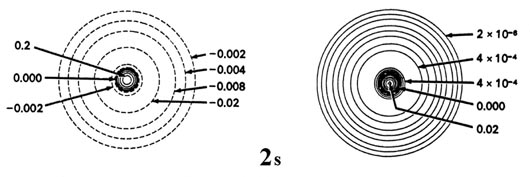

Nosotros could also represent the distribution of negative accuse in the hydrogen atom in the manner used previously for the electron confined to movement on a aeroplane, Fig. ii-4, by displaying the charge density in a plane by ways of a profile map. Imagine a aeroplane through the atom including the nucleus. The density is calculated at every indicate in this plane. All points having the same value for the electron density in this plane are joined by a contour line (Fig. 3-6). Since the electron density depends but on r, the distance from the nucleus, and not on the management in space, the contours will be circular. A contour map is useful every bit information technology indicates the "shape" of the density distribution.

| Fig. 3-6. (a) A contour map of the electron density distribution in a plane containing the nucleus for the n = 1 level of the H cantlet. The distance between next contours is one au. The numbers on the left-hand side on each contour requite the electron densityin au. The numbers on the right-hand side give the fraction of the total electronic charge which lies within a sphere of that radius. Thus 99% of the single electronic accuse of the H atom lies within a sphere of radius 4 au (or diameter = 4.two ´x -eight cm). (b) This is a profile of the contour map along a line through the nucleus. It is, of course, the same every bit that given previously in Fig. 3-4 for P 1 , but at present plotted from the nucleus in both directions. |

This completes the clarification of the virtually stable country of the hydrogen atom, the state for which n = 1. Before proceeding with a word of the excited states of the hydrogen atom we must introduce a new term. When the energy of the electron is increased to some other of the allowed values, corresponding to a new value for n, y north and Pnorthward change as well. The moving ridge functions y n for the hydrogen atom are given a special name, atomic orbitals , because they play such an important part in all of our future discussions of the electronic structure of atoms. In general the discussion orbital is the proper name given to a wave function which determines the motion of a unmarried electron. If the one-electron wave function is for an atomic system, it is called an atomic orbital. (Click here for note.)

For every value of the energy Eastward n , for the hydrogen atom, in that location is a degeneracy equal to due north two . Therefore, for due north = 1, at that place is merely ane diminutive orbital and one electron density distribution. Withal, for n = two, in that location are four different diminutive orbitals and four unlike electron density distributions, all of which possess the same value for the energy, E 2. Thus for all values of the chief quantum number northward there are northward ii dissimilar means in which the electronic charge may be distributed in iii-dimensional space and even so possess the same value for the energy. For every value of the chief quantum number, one of the possible atomic orbitals is independent of direction and gives a spherical electron density distribution which can be represented by circular contours as has been exemplified in a higher place for the case of n = 1. The other diminutive orbitals for a given value of n showroom a directional dependence and predict density distributions which are not spherical but are concentrated in planes or forth certain axes. The athwart dependence of the atomic orbitals for the hydrogen atom and the shapes of the contours of the respective electron density distributions are intimately connected with the angular momentum possessed by the electron.

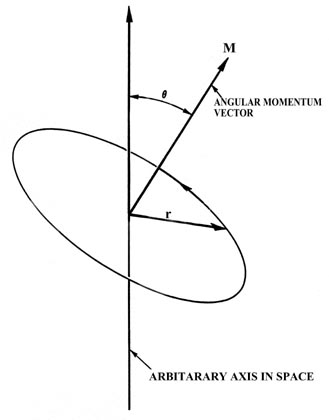

The concrete quantity known every bit angular momentum plays a ascendant part in the understanding of the electronic construction of atoms. To proceeds a concrete picture and feeling for the angular momentum information technology is necessary to consider a model organisation from the classical point of view. The simplest classical model of the hydrogen atom is one in which the electron moves in a circular orbit with a abiding speed or athwart velocity (Fig. three-7). Just as the ordinary momentum m 5 plays a dominant part in the analysis of straight line or linear motion, so angular momentum plays the central role in the analysis of a arrangement with circular motion as institute in the model of the hydrogen cantlet.

Fig. 3-7. The angular momentum vector for a classical model of the atom.

In Fig. iii-7, m is the mass of the electron, 5 is the linear velocity (the velocity the electron would possess if information technology continued moving at a tangent to the orbit equally indicated in the figure) and r is the radius of the orbit. The linear velocity v is a vector since it possesses at whatever instant both a magnitude and a direction in space. Manifestly, equally the electron rotates in the orbit the direction of five is constantly irresolute, and thus the linear momentum m 5 is not constant for the circular movement. This is then even though the speed of the electron (the magnitude of v which is denoted by u ) remains unchanged. According to Newton's 2nd law, a force must be acting on the electron if its momentum changes with time. This is the force which prevents the electron from flying on tangent to its orbit. In an atom the attractive force which contains the electron is the electrostatic force of attraction between the nucleus and the electron, directed along the radius r at right angles to the direction of the electron's movement.

The angular momentum, like the linear momentum, is a vector and is defined as follows:

| |

The angular momentum vector M is directed forth the axis of rotation. From the definition information technology is evident that the angular momentum vector volition remain abiding as long as the speed of the electron in the orbit is constant ( u remains unchanged) and the airplane and radius of the orbit remain unchanged. Thus for a given orbit, the angular momentum is constant every bit long equally the athwart velocity of the particle in the orbit is constant. In an atom the only strength on the electron in the orbit is directed along r; it has no component in the management of the motion. The forcefulness acts in such a mode every bit to change only the linear momentum. Therefore, while the linear momentum is not abiding during the round motion, the angular momentum is. A force exerted on the particle in the direction of the vector v would change the athwart velocity and the angular momentum. When a forcefulness is applied which does change G, a torque is said to be acting on the system. Thus angular momentum and torque are related in the aforementioned way every bit are linear momentum and force.

The important betoken of the above discussion is that both the angular momentum and the free energy of an atom remain constant if the atom is left undisturbed. Whatever physical quantity which is abiding in a classical organisation is both conserved and quantized in a quantum mechanical system. Thus both the energy and the angular momentum are quantized for an atom.

In that location is a breakthrough number, denoted past 50, which governs the magnitude of the angular momentum, just as the quantum number n determines the free energy. The magnitude of the athwart momentum may assume only those values given by:

Furthermore, the value of n limits the maximum value of the angular momentum as the value of fifty cannot be greater than n - 1. For the land n = 1 discussed above, 50 may take the value of zero only. When due north = 2, fifty may equal 0 or 1, and for due north = 3, l = 0 or 1 or ii, etc. When fifty = 0, it is evident from equation (4) that the angular momentum of the electron is nada. The atomic orbitals which describe these states of zero angular momentum are called s orbitals. The southward orbitals are distinguished from one some other by stating the value of north, the principal quantum number. They are referred to as the 1s, iidue south, 3s, etc., atomic orbitals.

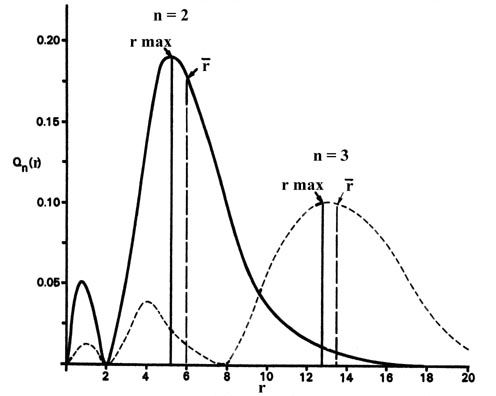

The preceding word referred to the idue south orbital since for the basis land of the hydrogen atom n = 1 and l = 0. This orbital, and all s orbitals in full general, predict spherical density distributions for the electron as exemplified by Fig. iii-v for the 1s density. Figure 3-8 shows the radial distribution functions Q(r) which utilize when the electron is in a 2s or threes orbital to illustrate how the character of the density distributions change as the value of n is increased. (Click hither for note.)

Fig. 3-8. Radial distribution functions for the twos and 3s density distributions.

Comparing these results with those for the 1southward orbital in Fig. 3-5 nosotros meet that as n increases the average value of r increases. This agrees with the fact that the free energy of the electron besides increases equally n increases. The increased energy results in the electron being on the average pulled further away from the attractive strength of the nucleus. Every bit in the elementary example of an electron moving on a line, nodes (values of r for which the electron density is null) appear in the probability distributions. The number of nodes increases with increasing energy and equals northward - ane.

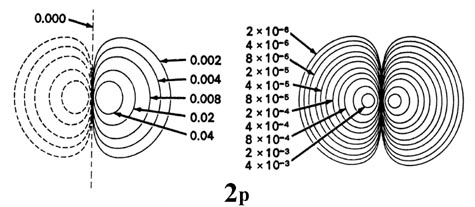

When the electron possesses angular momentum the density distributions are no longer spherical. In fact for each value of l, the electron density distribution assumes a characteristic shape (Fig. iii-9).

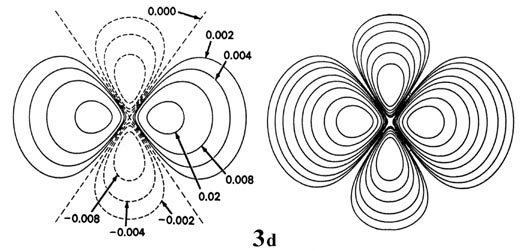

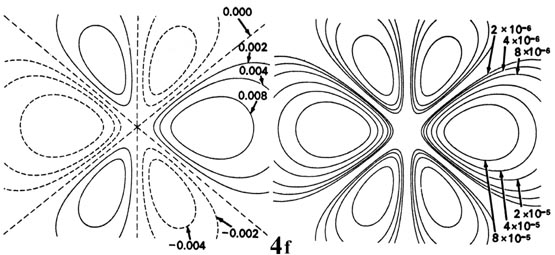

Fig. 3-9. Contour maps of the iisouthward, iip, threed and 4f atomic orbitals and their charge density distributions for the H cantlet. The zero contours shown in the maps for the orbitals ascertain the positions of the nodes. Negative values for the contours of the orbitals are indicated by dashed lines, positive values by solid lines.

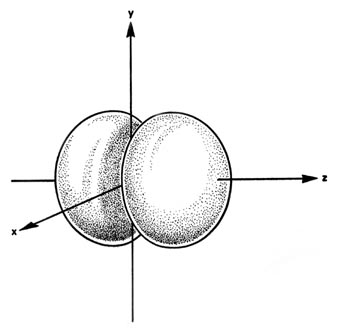

When l = i, the orbitals are called p orbitals. In this case the orbital and its electron density are concentrated along a line (centrality) in space. The 2p orbital or wave role is positive in value on i side and negative in value on the other side of a plane which is perpendicular to the axis of the orbital and passes through the nucleus. The orbital has a node in this aeroplane, and consequently an electron in a twop orbital does not place any electronic charge density at the nucleus. The electron density of a ones orbital, on the other hand, is a maximum at the nucleus. The aforementioned diagram for the iip density distribution is obtained for any plane which contains this centrality. Thus in three dimensions the electron density would appear to exist concentrated in two lobes, one on each side of the nucleus, each lobe being circular in cross department (Fig. 3-10).

Fig. three-10. The appearance of the 2p electron density distribution in iii-dimensional space.

When l = 2, the orbitals are called d orbitals and Fig. iii-ix shows the contours in a aeroplane for a iiid orbital and its density distribution. Notice that the density is again cypher at the nucleus and that there are now 2 nodes in the orbital and in its density distribution. As a final example, Fig. three-9 shows the contours of the orbital and electron density distribution obtained for a 4f diminutive orbital which occurs when n = 4 and l = iii. (Click here for note.) The signal to notice is that as the athwart momentum of the electron increases, the density distribution becomes increasingly concentrated along an centrality or in a plane in space. Just electrons in s orbitals with zero angular momentum give spherical density distributions and in addition place accuse density at the position of the nucleus.

We have not as nevertheless accounted for the full degeneracy of the hydrogen atom orbitals which we stated earlier to be due north two for every value of n. For case, when n = 2, there are four distinct atomic orbitals. The remaining degeneracy is once again determined past the angular momentum of the organisation. Since angular momentum similar linear momentum is a vector quantity, nosotros may refer to the component of the angular momentum vector which lies forth some chosen axis. For reasons we shall investigate, the number of values a particular component tin presume for a given value of l is (2l + 1). Thus when l = 0, there is no angular momentum and there is but a single orbital, an s orbital. When fifty = 1, there are three possible values for the component (two´ 1 + 1) of the total angular momentum which are physically distinguishable from ane another. There are, therefore, three p orbitals. Similarly in that location are five d orbitals, (2 ´ 2+1), seven f orbitals, (ii ´ three +1), etc. All of the orbitals with the same value of north and l, the three 2p orbitals for instance, are similar but differ in their spatial orientations.

To gain a better understanding of this final element of degeneracy, we must consider in more detail what quantum mechanics predicts concerning the athwart momentum of an electron in an atom.

Source: https://www.chemistry.mcmaster.ca/esam/Chapter_3/section_2.html

Postar um comentário for "How to Read Radial Probability Distribution Graph"